Quantifying Uncertainty in Inferences in Physics and Astronomy ¶

P.B. Stark, Department of Statistics, UC Berkeley¶

Kavli IPMU – Berkeley Symposium: "Statistics, Physics and Astronomy"

Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe¶

Tokyo, Japan¶

11–12 January 2018

Joint work with Steve Evans, Chris Genovese, Nicolas Hengartner, Mikael Kuusela, Bob Parker, Chad Schafer, Luis Tenorio, ...¶

Inverse problems¶

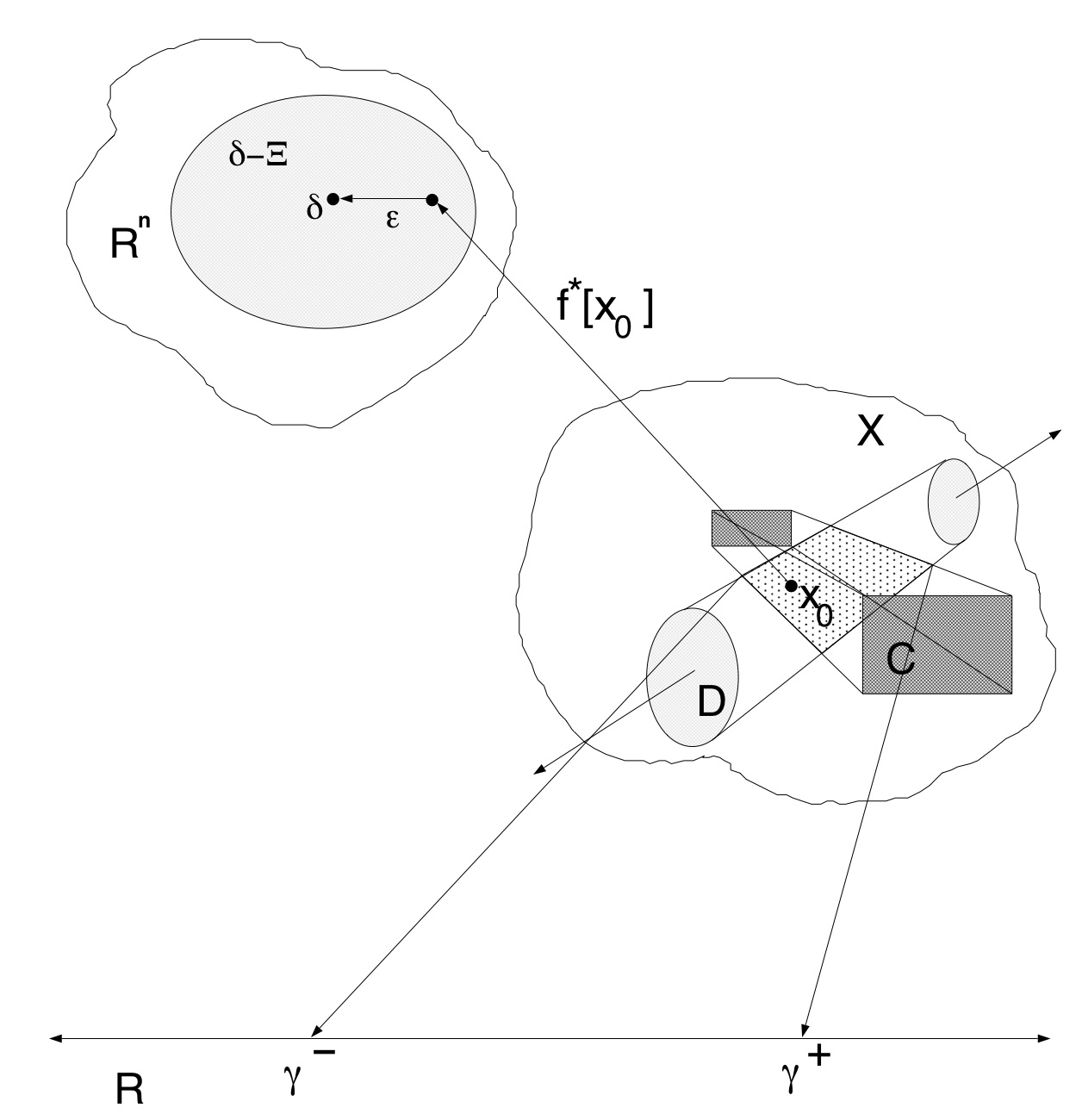

Observe finite number of noisy data $\delta$ indirectly related to an unknown "object" $x_0$ by some (approximately) known transformation $f$.

- $\delta = f[x_0] + \epsilon$

- In many problems in physics, astronomy, and other natural sciences, $x_0$ is a function, an infinite-dimensional object.

- spectrum

- physical parameter that varies as a function of position, time, energy, or some other variable

- Common to discretize $x_0$

- Pixels/voxels, bins, polynomials, truncated Fourier series, truncated SVD, principal components, ...

- Also common to regularize

- stop iterative methods before convergence, Tichonov regularization, smoothing/seminorm minimization, $\ell_1$ minimization, thresholding, truncating infinite expansions

- Discretization & regularization artifically reduce formal uncertainty; introduce unknown/uncontrolled bias.

- Better to focus on inference than on estimation.

- Generally, $f$ has an infinite-dimensional null space: infinitely many models would produce identical data: $x_0$ not identifiable.

For many scientific purposes, suffices to make inferences about functionals (parameters) $g[x_0]$.

- E.g., local averages of $x_0$, number of modes of $x_0$, total "energy" of $x_0$, etc.

- Well-posed questions in ill-posed problems

Often have physical constraints on $x_0$ in addition to the data: know $x_0 \in \mathcal{C}$.

- Can greatly reduce the uncertainty in inferences about $g[x_0]$

- Non-negativity, monotonicity, upper bounds, energy bounds, etc.

Focus on linear $f$, additive errors $\epsilon$, convex constraints $\mathcal{C}$.

No assumption about joint probability distribution of $\epsilon$

Assume can bound $\epsilon$ probabilistically: know a set $\Xi$ s.t. $\Pr \{ \epsilon \in \Xi \} \ge 1-\alpha$.

$\epsilon$ can include systematic error

Can account for (possible) dependence among components of $\epsilon$

Examples¶

de-blurring, signal recovery, spectrum estimation, tomography, remote sensing, deconvolution

Downward continuation of potential fields from noisy measurements

Inverting Abel's equation in travel-time seismology and normal-mode helioseismology

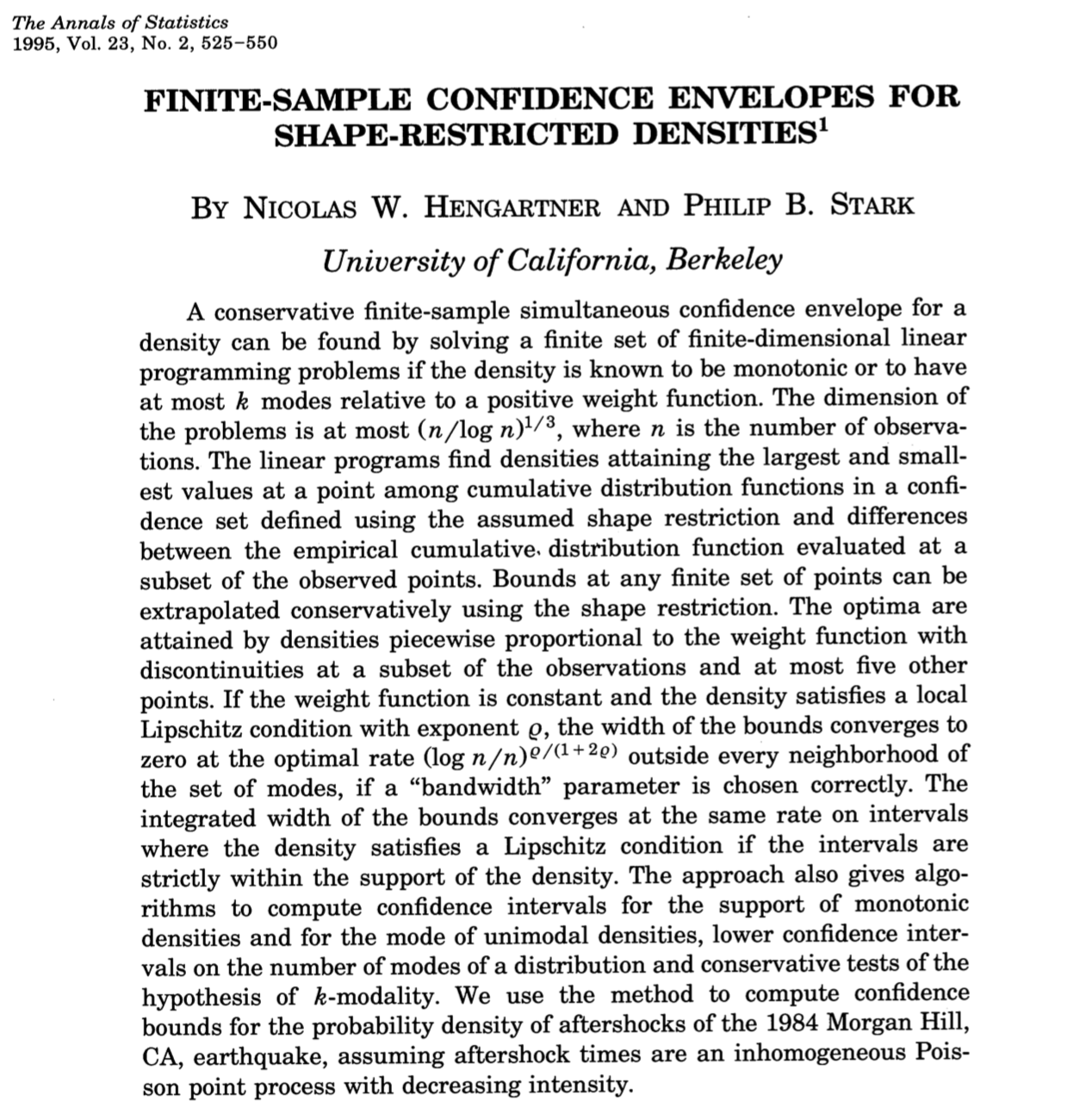

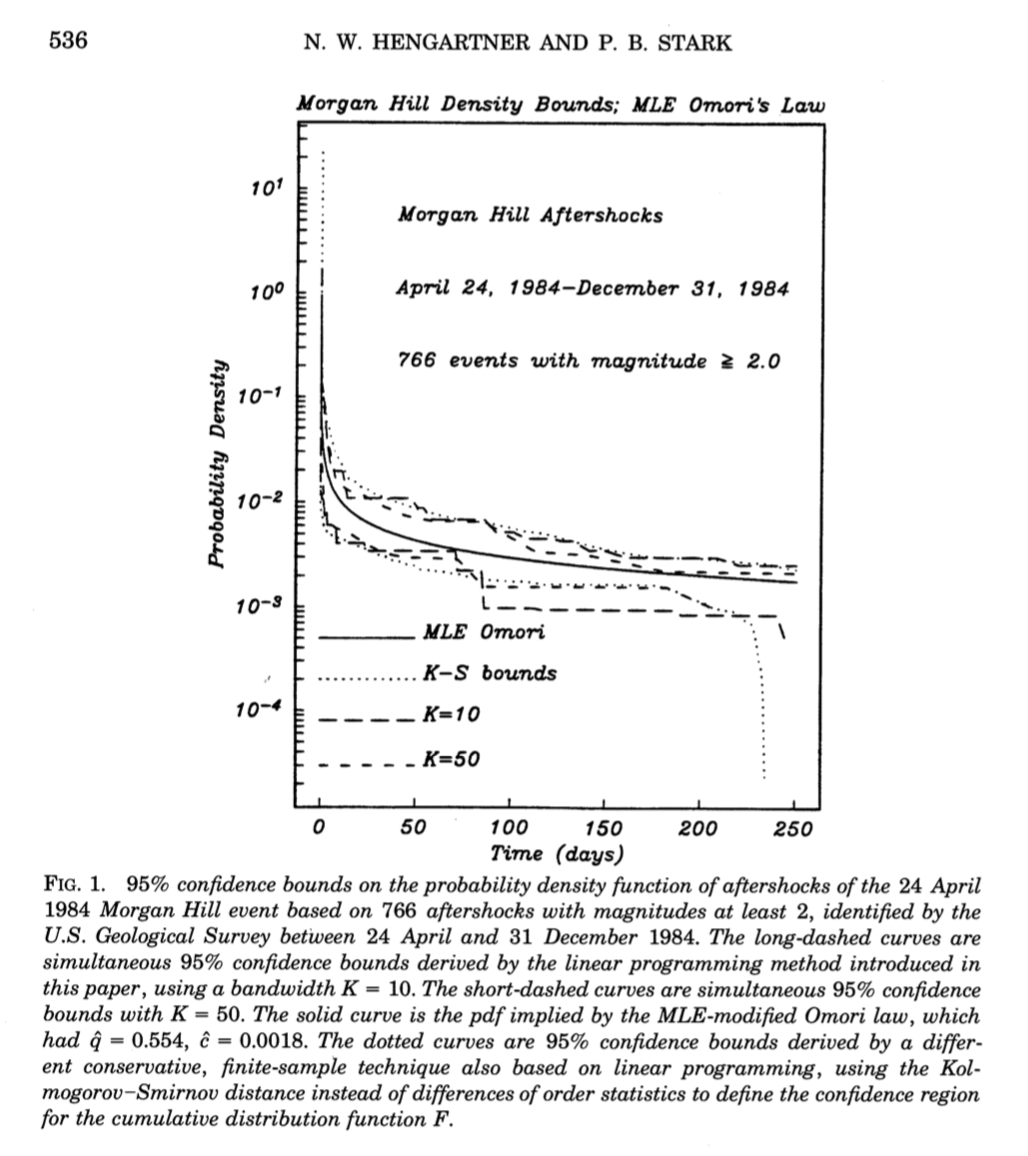

Bounds on probability densities using constraints such as monotonicity, unimodality, $\le k$-modality; finding a lower confidence bound on the number of modes of a pdf

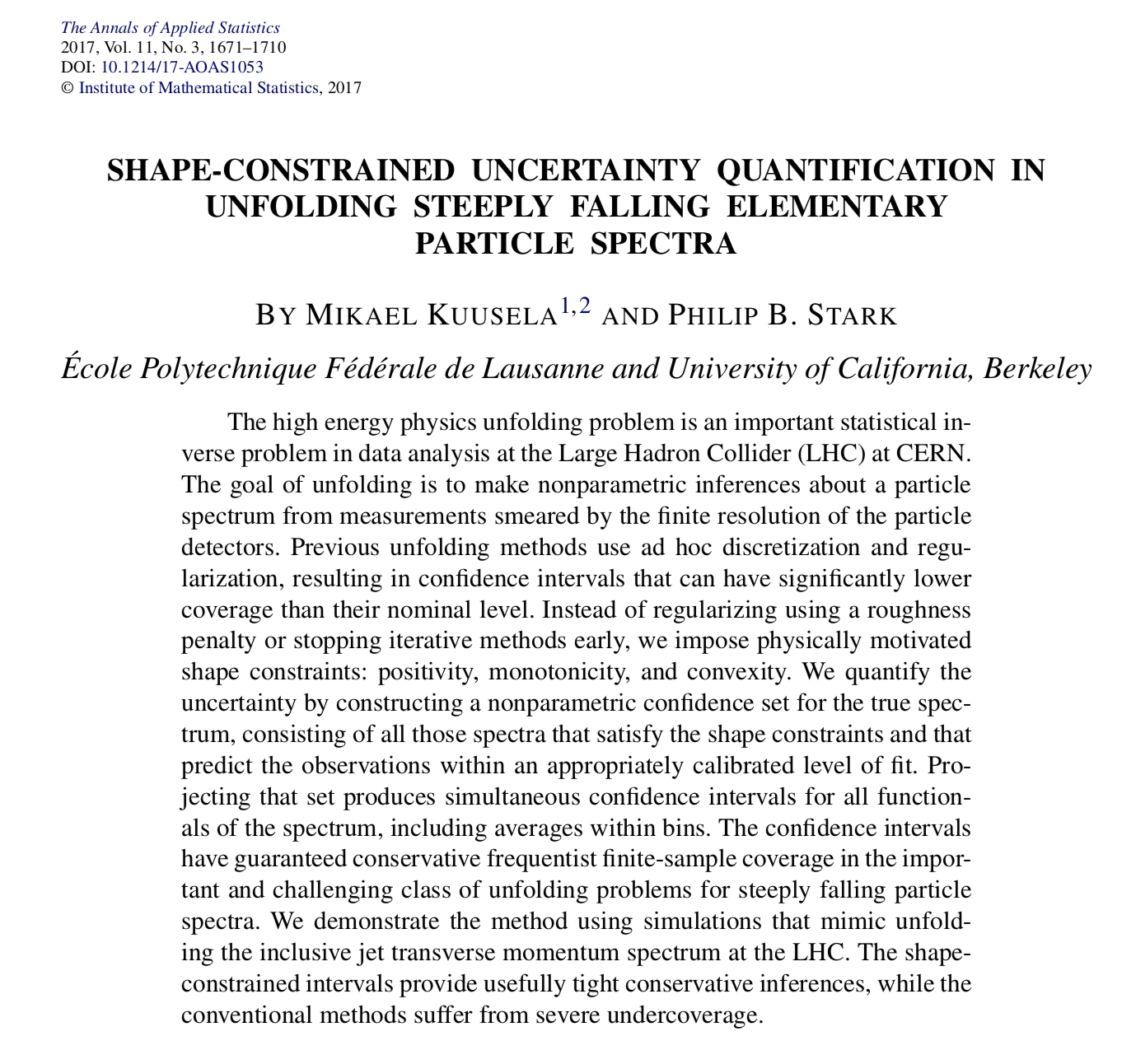

The HEP "unfolding problem" (Poisson deconvolution)

Notation¶

$\mathcal{X}$ a real linear vector space ("models")

$x_0 \in \mathcal{X}$ ("true model")

$\mathcal{X}^*$ algebraic dual of $\mathcal{X}$

$\mathbf{f}^*$ an $n$-tuple of elements of $\mathcal{X}^*$, linear functionals on $\mathcal{X}$ ("data mapping")

$\delta = \mathbf{f}^*[x_0] + \epsilon$ ("data")

$\Xi \subset \Re^n$

- satisfies $\Pr \{ \epsilon \in \Xi \} \ge 1-\alpha$

- is a ball in some weighted $p$ norm: $\{ \gamma \in \Re^n: \| \gamma \|_p^{\Sigma^{-1}}\leq \chi \}$

- $p = 1$, $p=2$, and $p=\infty$ lead to linear or quadratic programming problems

$\mathcal{C} \subset \mathcal{X}$ ("constraints")

$\mathcal{D} \equiv \{ x \in \mathcal{X}: \mathbf{f}^*[x] \in \delta - \Xi \}$ (models that fit the data adequately)

$g: \mathcal{C} \rightarrow \Re$ a functional on $\mathcal{X}$ (a parameter of interest)

$\mathcal{D} \ni x_0$ whenever $\Xi \ni \epsilon$, which has chance $\ge 1-\alpha$.

Whenever $\mathcal{D} \ni x_0$, $\mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D} \ni x_0$, because $x_0 \in \mathcal{C}$.

Thus

$$\Pr \{ \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D} \ni x_0 \} \ge 1-\alpha.$$

If $\mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D} \ni x_0$, then anything that is true for all $x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}$ is true for $x_0$.

In particular, $g[x_0] \in g[\mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}]$.

Strict bounds confidence intervals¶

$$ \gamma^- \equiv \inf_{x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}} g[x] $$

$$ \gamma^+ \equiv \sup_{x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}} g[x] $$

Then $\mathcal{I}_g \equiv [\gamma^-, \gamma^+]$ is a $1-\alpha$ confidence interval for $g[x_0]$.

For any collection $\{g_\beta \}_{\beta \in B}$, countable or uncountable, $\{\mathcal{I}_{g_\beta} \}_{\beta \in B}$ have simultaneous coverage probability:

$$ \Pr \left \{ \mathcal{I}_{g_\beta} \ni g_\beta[x_0],\;\; \forall \beta \in B \right \} \ge 1-\alpha. $$

Solving the optimization problems¶

- The optimization problems have infinite-dimensional unknowns.

- Discretizing $\mathcal{X}$ gives lower bounds on the uncertainty: not every $x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}$ can be represented.

Using duality can give upper bounds on the uncertainty.

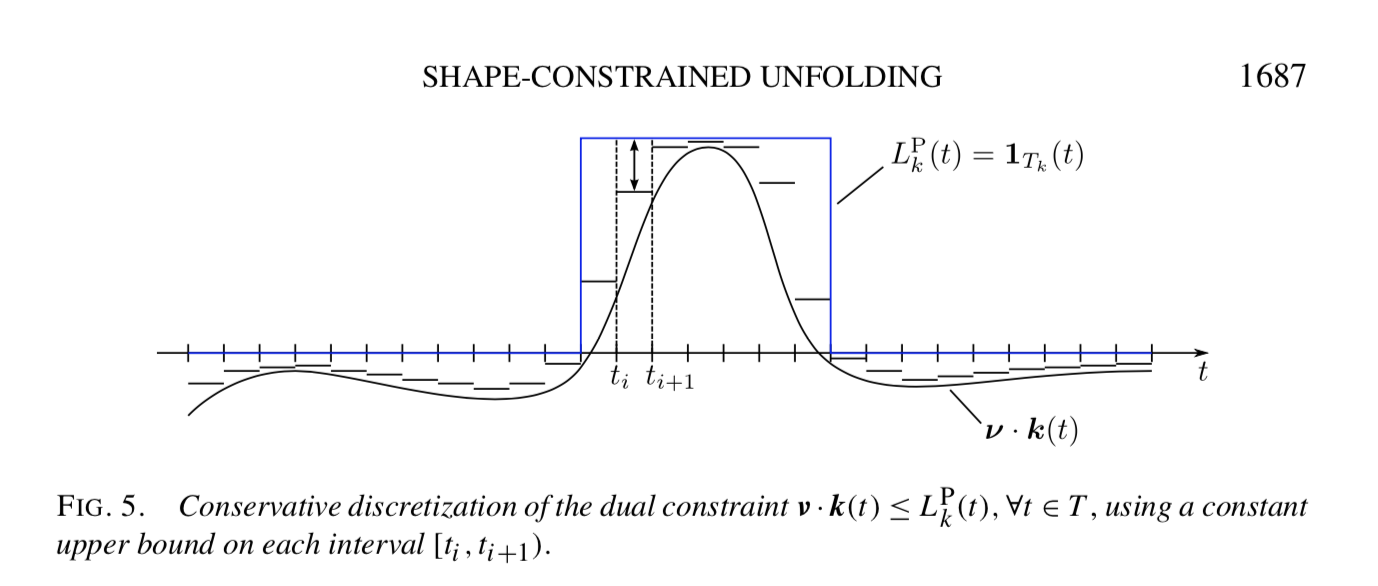

The dual problems have finite-dimensional unknowns, but infinite-dimensional constraints.

Possible to discretize the dual in a conservative way, so that solution to discretized dual gives upper bound on the uncertainty.

For linear $f$, $g$, convex $\Xi$, convex $\mathcal{C}$, get convex programming problems, for which there are good algorithms

Fenchel Duality¶

Let $x^*$ be any element of $X^*$.

\begin{eqnarray*} v({\mathcal{P}})&\equiv&\inf_{x\in \mathcal{C}\cap\mathcal{D}} g[x] \\ &=&\inf_{x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}}\{ x^* [x] + (g-x^* )[x] \} \\ &\geq& \inf_{x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}} x^* [x] +\inf_{x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}}\{ (g-x^* )[x]\} \\ &\geq& \inf_{x \in \mathcal{D}} x^* [x] + \inf_{x \in \mathcal{C}} \{ (g-x^* )[x]\}. \end{eqnarray*}

But $x^*$ was arbitrary, so $$ \inf_{x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}} g[x] \geq \sup_{x^* \in x^* } \left \{ \inf_{x \in \mathcal{D}} x^* [x] + \inf_{x \in \mathcal{C}} \{ (g-x^* )[x] \} \right \} $$ $$ = \sup_{x^* \in x^* } \{D^* [x^* ] + C^* [x^* ] \},\ $$

where $$ C^* [x^* ]\equiv \inf_{x \in \mathcal{C}} (g-x^* )[x]. $$ $$ D^* [x^* ]\equiv \inf_{x \in \mathcal{D}} x^* [x]. $$

Equality is possible (Fenchel's duality theorem and Lagrangian duality)

Define $ \mathcal{C}^* \equiv \{x^* \in x^* : C^* [x^* ] > -\infty \} $

$ \mathcal{D}^* \equiv \{x^* \in x^* : D^* [x^* ] > -\infty \}. $

$x^*$ gives a nontrivial bound if and only if $x^* \in \mathcal{C}^*\cap\mathcal{D}^*$.

The only functionals $x^*$ bounded below on $\mathcal{D}$ are linear combinations of the data functionals $f_j^*$ $$ x^* = \lambda\cdot\mathbf{f}^* , \;\; \lambda \in \Re^n . $$

For $x\in\mathcal{D}$, $\mathbf{f}^* [x]=\delta + \gamma$, where $|| \gamma ||_p^{\Sigma^{-1}}\leq \chi$. Thus

\begin{eqnarray} \lambda\cdot\mathbf{f}^* [x] &=& \lambda\cdot\delta + \lambda\cdot\gamma \nonumber \\ &\geq& \lambda\cdot\delta - | \lambda\cdot\gamma | \nonumber \\ &\geq& \lambda \cdot \delta - || \lambda ||_q^{\Sigma} ||\gamma ||_p^{\Sigma^{-1}}. \end{eqnarray}

Fundamental duality inequality for strict bounds¶

$$ \inf_{x \in \mathcal{C} \cap \mathcal{D}} g[x] \geq \sup_{\lambda \in \Re^n} \left \{ \lambda \cdot \delta - \chi||\lambda ||_q^{\Sigma} + C^* [ \lambda\cdot\mathbf{f}^* ] \right \}. $$

$C^*$ is a concave functional if $\mathcal{C}$ is convex.

Computing $C^*$ in general is a semi-infinite programming problem with finite-dimensional unknown and infinitely many constraints.

Generalizations¶

uncertainty in the data mapping $\mathbf{f}^*$

nonlinear parameters (e.g., number of modes, energy, etc.)

optimizing $\mathcal{D}$

nonconvex $\mathcal{C}$

Limitations of strict bounds¶

Optimality

- In general, need to tailor $\Xi$ to get optimal rates of convergence. See Hengartner & Stark (1995)

Convergence/consistency

- In general, need to combine measurements in such a way that the SNR increases as the number of data increases. See Genovese & Stark (1996), Evans & Stark (2002)

- Unless $\mathcal{C}$ and $\mathcal{D}$ are convex (and $g$ is suitable), might be no guarantee of finding global optimum—but still possible to get conservative bounds

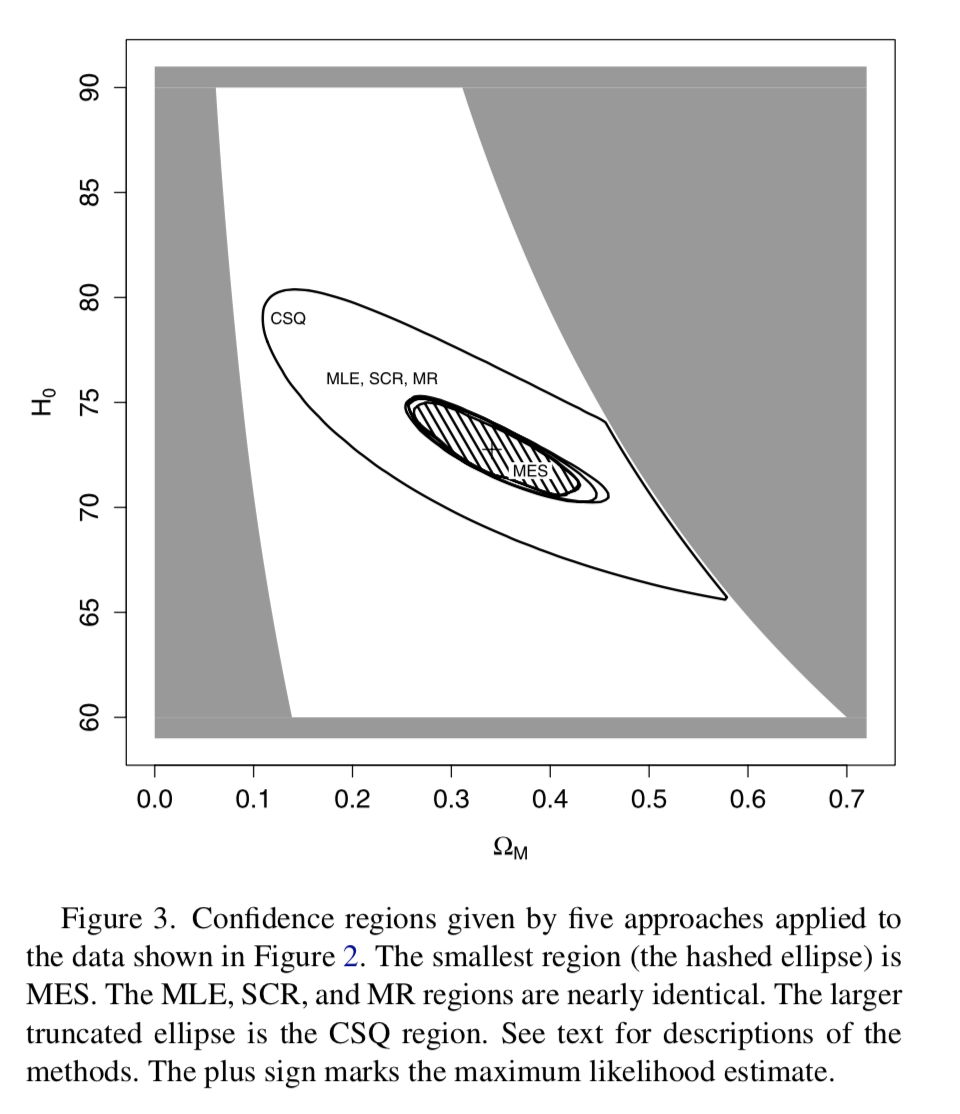

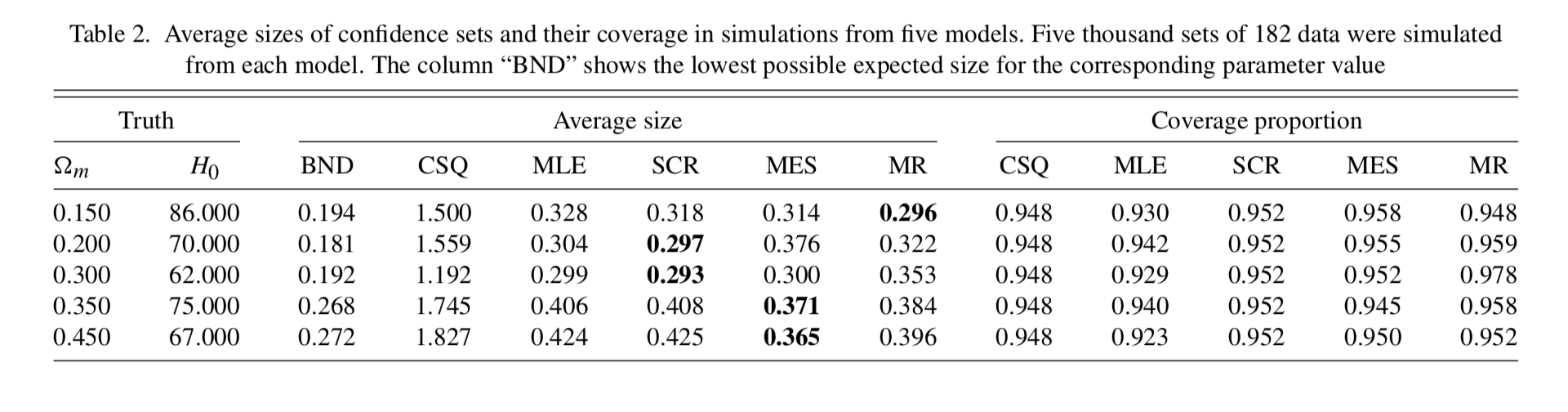

Minimax expected size confidence sets¶

Among all procedures for constructing a valid $1-\alpha$ confidence set for a parameter, which has the smallest worst-case expected size?

Exploit duality between Bayesian and frequentist methods: least-favorable prior.

Minimax confidence intervals for Gauss coefficients of the geomagnetic field¶

Measure field at surface and with satellites.

Interested spherical harmonic decomposition of field at CMB

Downward continuation problem

Constraints

- energy dissipated by field is less than Earth's total surface heat flow

- energy stored in field is not larger than Earth's rest mass

| $\ell$ | rms $x_\ell^m$ | Backus Interval | minimax bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 107.77 | 0.009 | 0.0055 |

| 2 | 22.59 | 0.015 | 0.0087 |

| 3 | 23.01 | 0.024 | 0.0148 |

| 4 | 17.86 | 0.042 | 0.0258 |

| 5 | 11.96 | 0.075 | 0.0458 |

| 6 | 9.36 | 0.135 | 0.0824 |

| 7 | 7.93 | 0.25 | 0.1500 |

| 8 | 4.73 | 0.45 | 0.2752 |

| 9 | 6.78 | 0.83 | 0.5080 |

| 10 | 4.59 | 1.53 | 0.9423 |

| 11 | 4.34 | 2.85 | 1.7555 |

| 12 | 3.62 | 5.32 | 3.2816 |

Average estimated Gauss coefficients, length of Backus' confidence intervals, lower bounds on lengths of nonlinearly based confidence intervals in microTesla, at 99.99% confidence, using the heat-flow bound. Columns 2 and 3 from Backus [1989]. Column 4 is NOT the length of a 99.99% confidence interval, merely a lower bound.

Bayesian approaches¶

Bayesian estimates¶

General approach (viz, don't even need data to make an estimate)

Guaranteed to have some good frequentist properties (if prior is proper and model dimension is finite)

Can be thought of as a kind of regularization

Elegant math from perspective of decision theory: convexify strategy space

Bayesian uncertainty estimates¶

Completely different interpretation than frequentist uncertainties

- Frequentist: hold parameter constant, characterize behavior under repeated measurement

- Bayesian: hold measurement constant, characterize behavior under repeatedly drawing parameter at random from the prior

Credible regions versus confidence regions

- credible level: probability that by drawing from prior, nature generates an element of the set, given the data

- confidence level: probability that procedure gives a set that contains the truth

- Can grade Bayesian methods using frequentist criteria

- E.g., what is the coverage probability of a credible region?

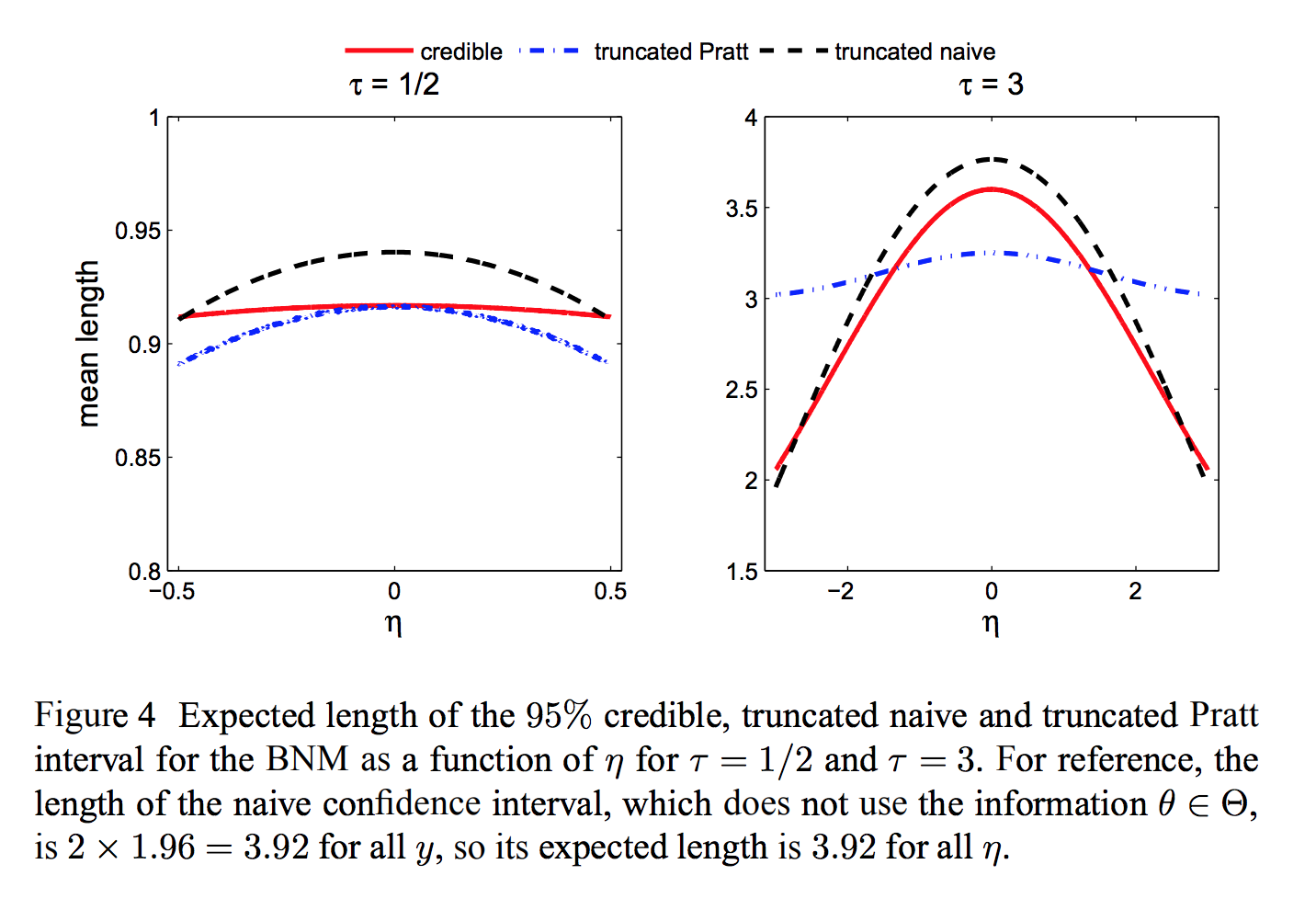

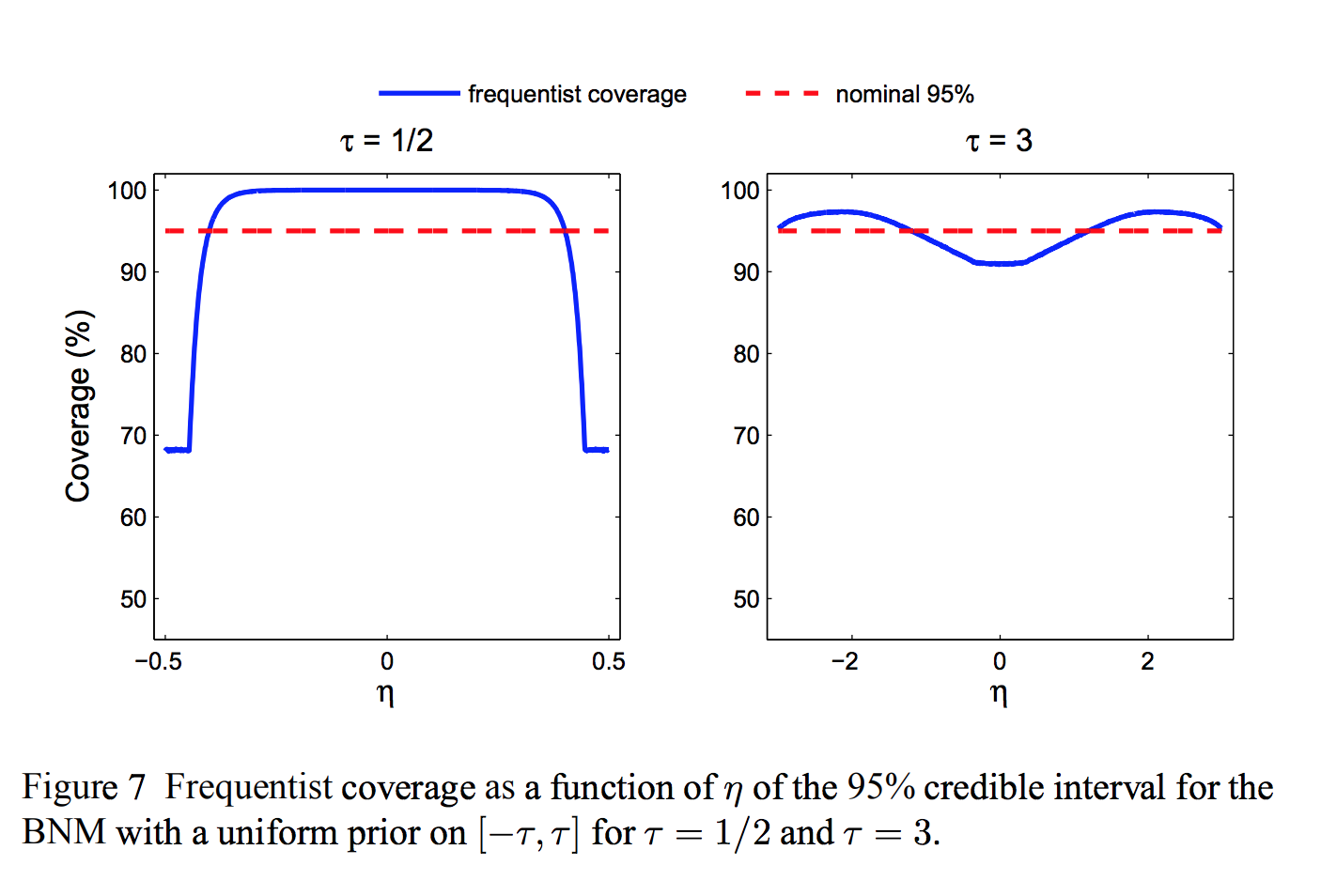

Toy problem: bounded normal mean¶

Observe $Y \sim N(\theta, 1)$.

Know a priori that $\theta \in [-\tau, \tau]$

Bayes "uninformative" prior: $\theta \sim U[-\tau, \tau]$

Duality between Bayes and minimax approaches¶

- Formal Bayesian uncertainty can be made as small as desired by choosing prior appropriately.

- Under suitable conditions, the minimax frequentist risk is equal to the Bayes risk for the "least-favorable" prior.

- If Bayes risk is less than minimax risk, prior is artificially reducing the (apparent) uncertainty. Regardless, means something different.

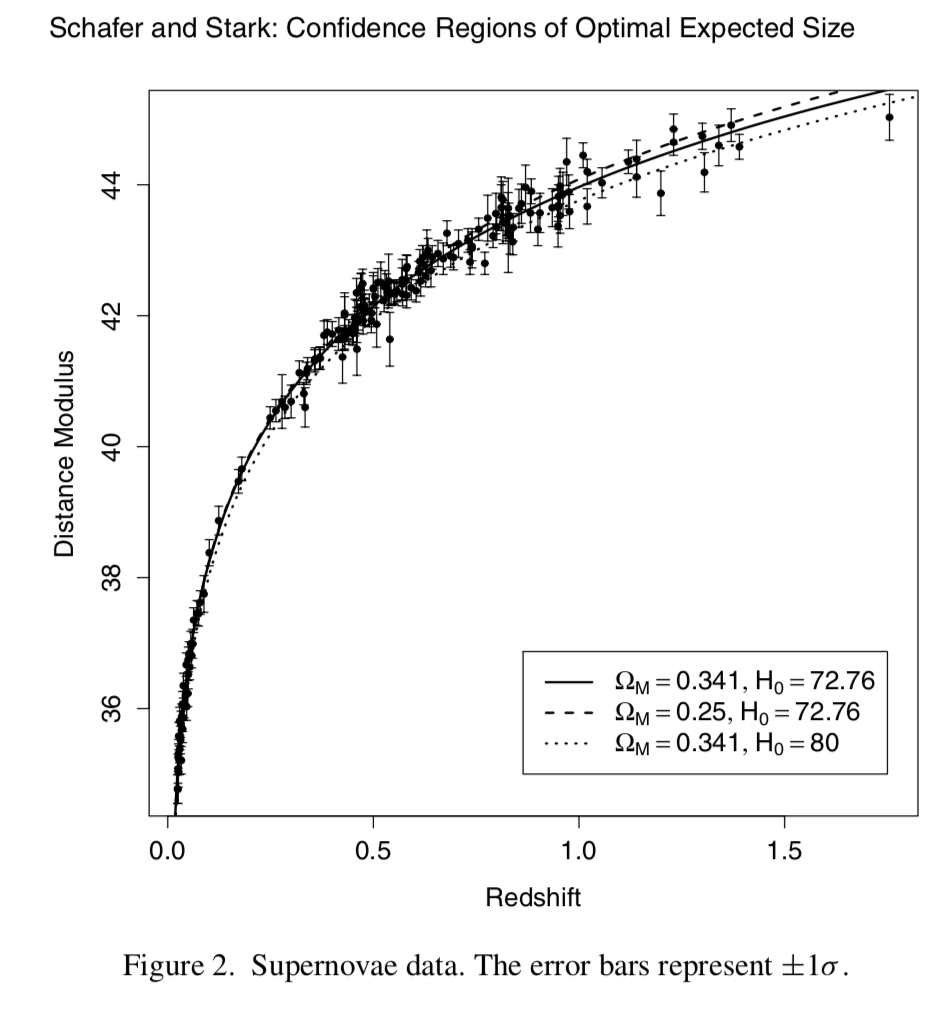

- Least-favorable prior can be approximated numerically even for "black-box" numerical models, a la Schafer & Stark (2009)

Posterior uncertainty measures meaningful only if you believe prior

Changes the subject

Is the truth unknown? Is it a realization of a known probability distribution?

Where does prior come from?

Usually chosen for computational convenience or habit, not "physics"

Priors get their own literature

Eliciting priors deeply problemmatic

Why should I care about your posterior, if I don't share your prior?

How much does prior matter?

Slogan "the data swamp the prior." Theorem has conditions that aren't always met.

Not all uncertainty can be represented by a probability

"Aleatory" versus "Epistemic"

Aleatory

- Canonical examples: coin toss, die roll, lotto, roulette

- under some circumstances, behave "as if" random (but not perfectly)

- Epistemic: stuff we don't know

Standard way to combine aleatory variability epistemic uncertainty puts beliefs on a par with an unbiased physical measurement w/ known uncertainty.

Claims by introspection, can estimate without bias, with known accuracy, just as if one's brain were unbiased instrument with known accuracy

Bacon put this to rest, but empirically:

- people are bad at making even rough quantitative estimates

- quantitative estimates are usually biased

- bias can be manipulated by anchoring, priming, etc.

- people are bad at judging weights in their hands: biased by shape & density

- people are bad at judging when something is random

- people are overconfident in their estimates and predictions

- confidence unconnected to actual accuracy.

- anchoring affects entire disciplines (e.g., Millikan, c, Fe in spinach)

what if I don't trust your internal scale, or your assessment of its accuracy?

same observations that are factored in as "data" are also used to form beliefs: the "measurements" made by introspection are not independent of the data

—George Box

Commonly ignored sources of uncertainty:

Coding errors (ex: Hubble)

Stability of optimization algorithms (ex: GONG)

"upstream" data reduction steps

Quality of PRNGs (RANDU, but still an issue)

| Expression | full | scientific notation |

|---|---|---|

| $2^{32}$ | 4,294,967,296 | 4.29e9 |

| $2^{64}$ | 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 | 1.84e19 |

| $2^{128}$ | 3.40e38 | |

| $2^{32 \times 624}$ | 9.27e6010 | |

| $13!$ | 6,227,020,800 | 6.23e9 |

| $21!$ | 51,090,942,171,709,440,000 | 5.11e19 |

| $35!$ | 1.03e40 | |

| $2084!$ | 3.73e6013 | |

| ${50 \choose 10}$ | 10,272,278,170 | 1.03e10 |

| ${100 \choose 10}$ | 17,310,309,456,440 | 1.73e13 |

| ${500 \choose 10}$ | 2.4581e20 | |

| $\frac{2^{32}}{{50 \choose 10}}$ | 0.418 | |

| $\frac{2^{64}}{{500 \choose 10}}$ | 0.075 | |

| $\frac{2^{32}}{7000!}$ | $<$ 1e-54,958 | |

| $\frac{2}{52!}$ | 2.48e-68 |

References¶

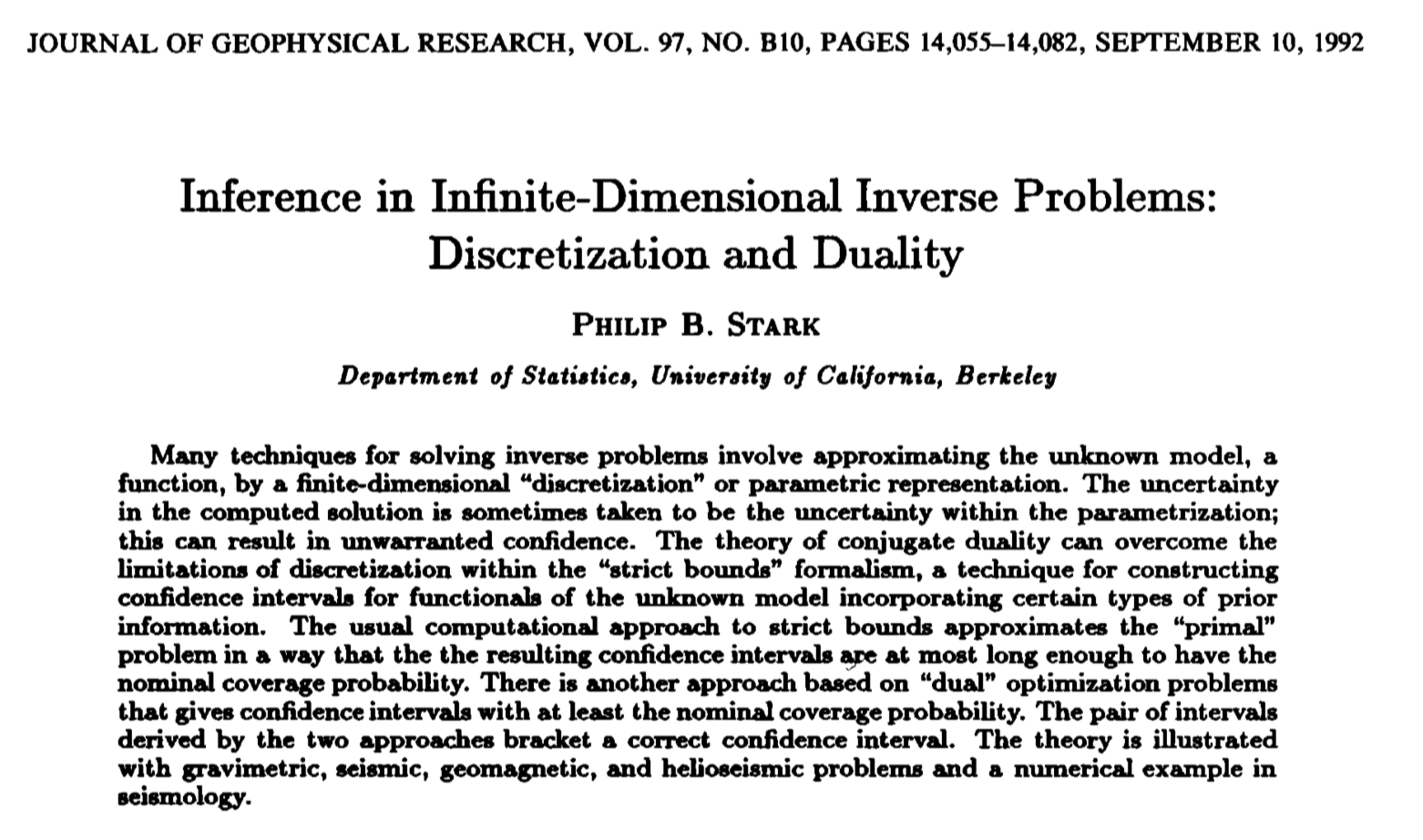

Stark, P.B., R.L. Parker, G. Masters, and J.A. Orcutt, 1986. Strict bounds on seismic velocity in the spherical Earth, Journal of Geophysical Research, 91, 13,892–13,902.

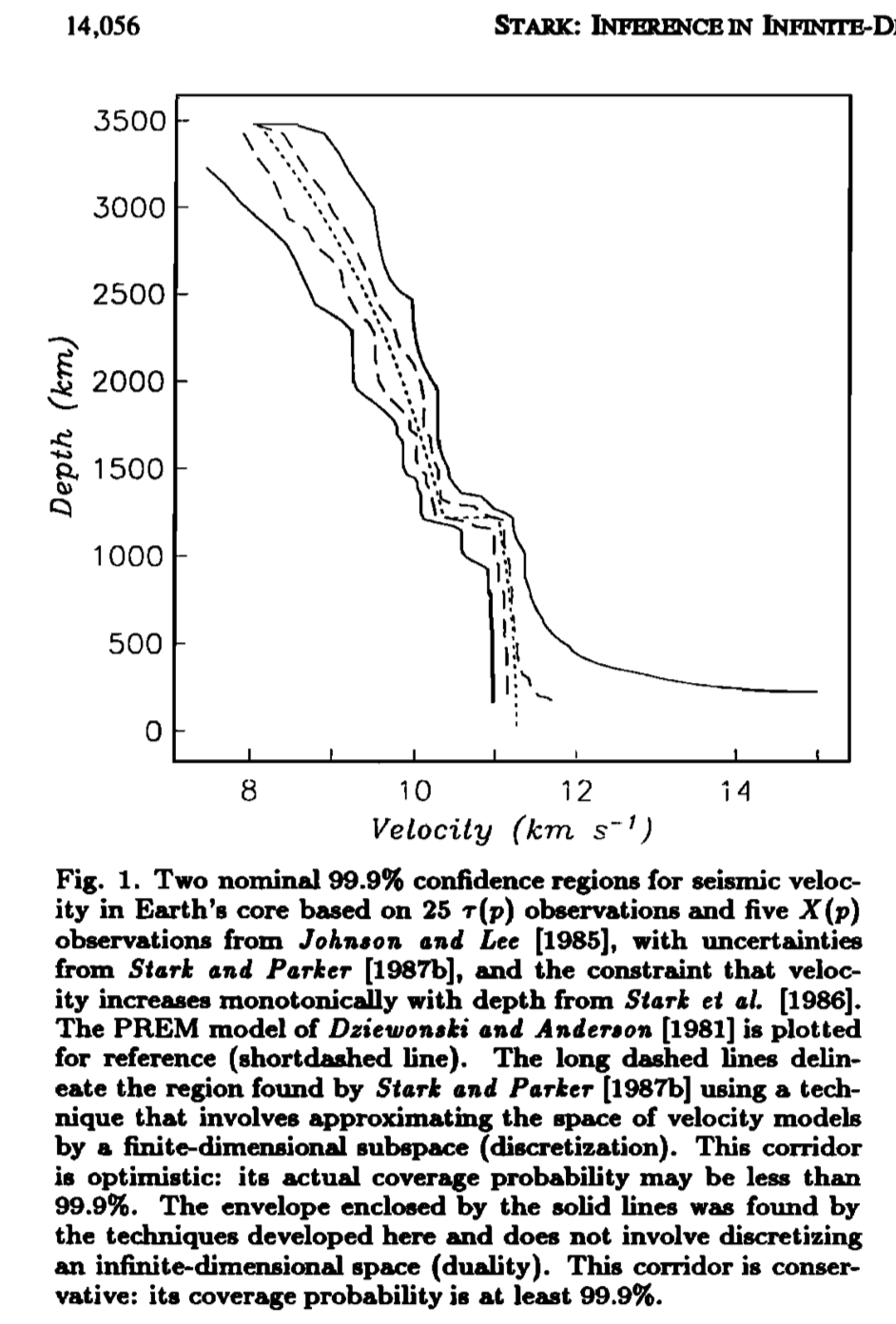

Stark, P.B., 1992. Minimax confidence intervals in geomagnetism, Geophysical Journal International, 108, 329–338. Stark, P.B., 1992. Inference in infinite-dimensional inverse problems: Discretization and duality, Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 14,055–14,082. Reprint: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/92JB00739/epdf

Stark, P.B., 1993. Uncertainty of the COBE quadrupole detection, Astrophysical Journal Letters, 408, L73–L76.

Hengartner, N.W. and P.B. Stark, 1995. Finite-sample confidence envelopes for shape-restricted densities, The Annals of Statistics, 23, 525–550.

Genovese, C.R. and P.B. Stark, 1996. Data Reduction and Statistical Consistency in Linear Inverse Problems, Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 98, 143–162.

Tenorio, L., P.B. Stark, and C.H. Lineweaver, 1999. Bigger uncertainties and the Big Bang, Inverse Problems, 15, 329–341.

Evans, S.N. and P.B. Stark, 2002. Inverse Problems as Statistics, Inverse Problems, 18, R55–R97. Reprint: http://iopscience.iop.org/0266-5611/18/4/201/pdf/0266-5611_18_4_201.pdf

Stark, P.B. and D.A. Freedman, 2003. What is the Chance of an Earthquake? in Earthquake Science and Seismic Risk Reduction, F. Mulargia and R.J. Geller, eds., NATO Science Series IV: Earth and Environmental Sciences, v. 32, Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 201–213. Preprint: https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/611.pdf

Evans, S.N., B. Hansen, and P.B. Stark, 2005. Minimax Expected Measure Confidence Sets for Restricted Location Parameters, Bernoulli, 11, 571–590. Also Tech. Rept. 617, Dept. Statistics Univ. Calif Berkeley (May 2002, revised May 2003). Preprint: https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/617.pdf

Stark, P.B., 2008. Generalizing resolution, Inverse Problems, 24, 034014. Reprint: https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/resolution07.pdf

Schafer, C.M., and P.B. Stark, 2009. Constructing Confidence Sets of Optimal Expected Size. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 104, 1080–1089. Reprint: https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/schaferStark09.pdf

Stark, P.B. and L. Tenorio, 2010. A Primer of Frequentist and Bayesian Inference in Inverse Problems. In Large Scale Inverse Problems and Quantification of Uncertainty, Biegler, L., G. Biros, O. Ghattas, M. Heinkenschloss, D. Keyes, B. Mallick, L. Tenorio, B. van Bloemen Waanders and K. Willcox, eds. John Wiley and Sons, NY. Preprint: https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/freqBayes09.pdf

Stark, P.B., 2015. Constraints versus priors. SIAM/ASA Journal on Uncertainty Quantification, 3(1), 586–598. doi:10.1137/130920721, Reprint: http://epubs.siam.org/doi/10.1137/130920721, Preprint: https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/constraintsPriors15.pdf

Stark, P.B., 2016. Pay no attention to the model behind the curtain. https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/eucCurtain15.pdf

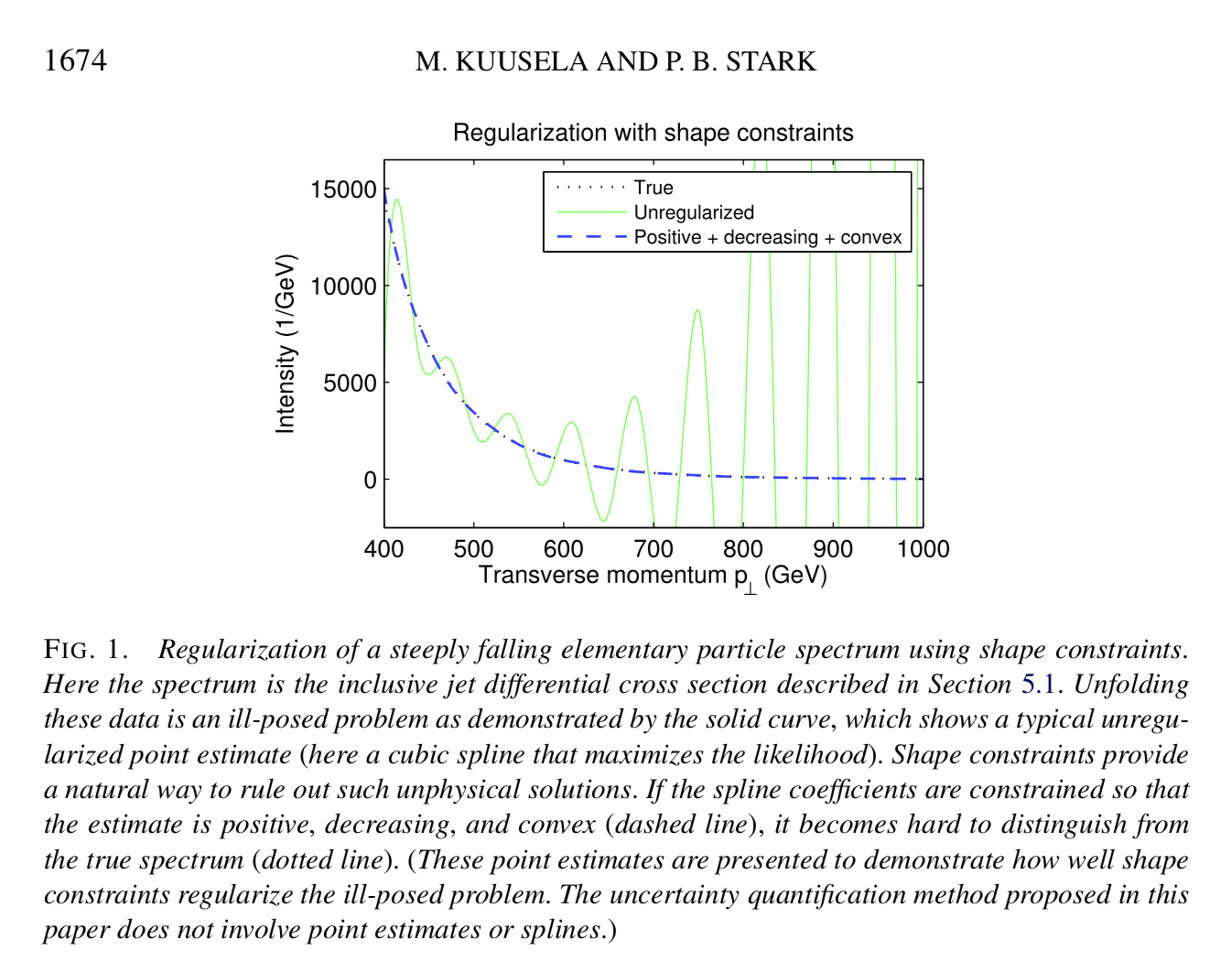

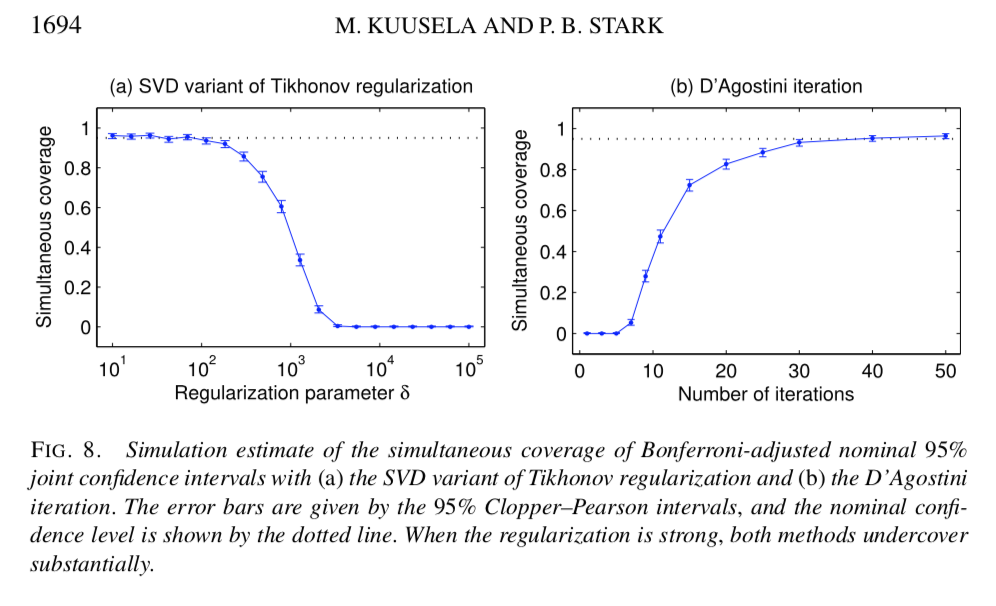

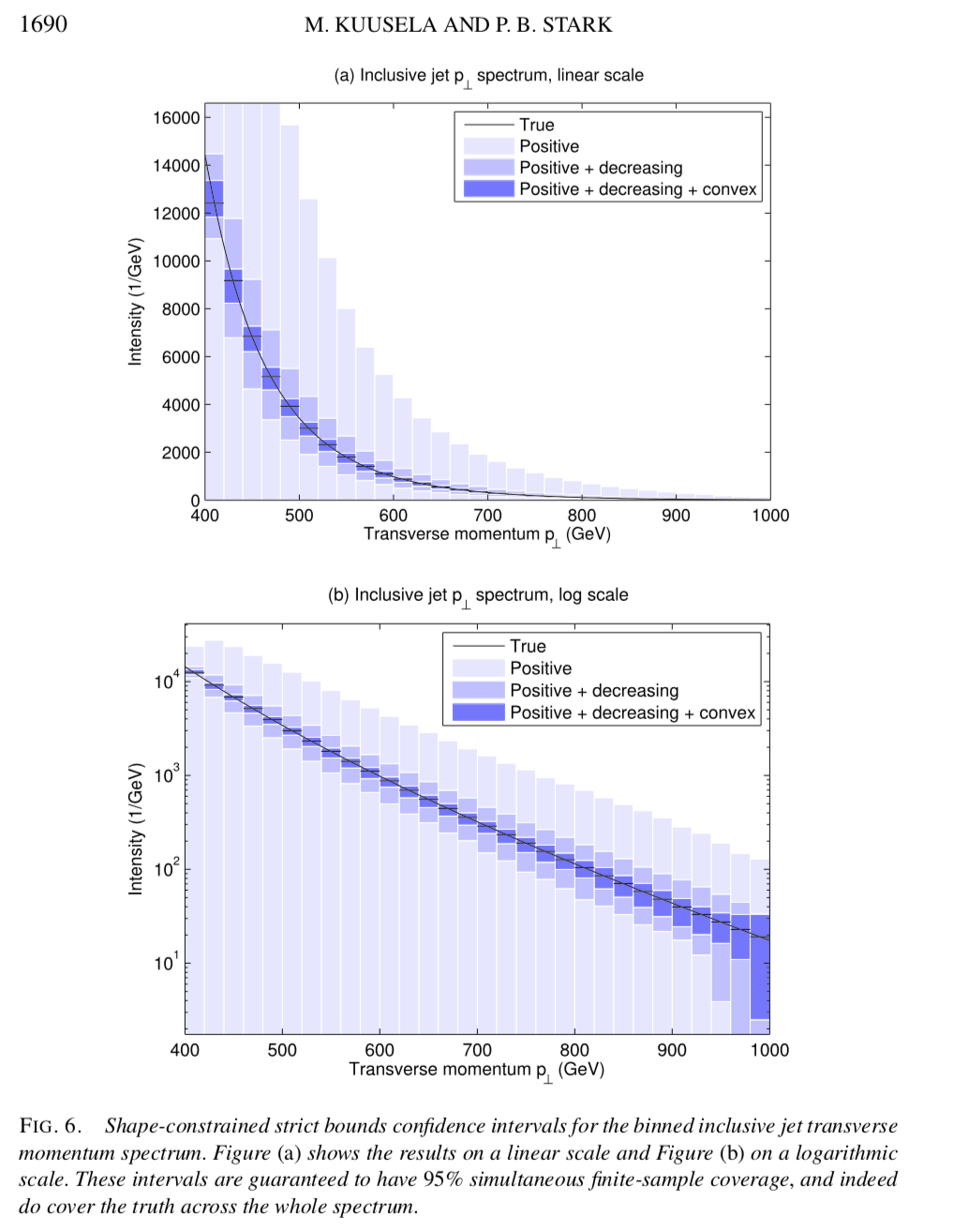

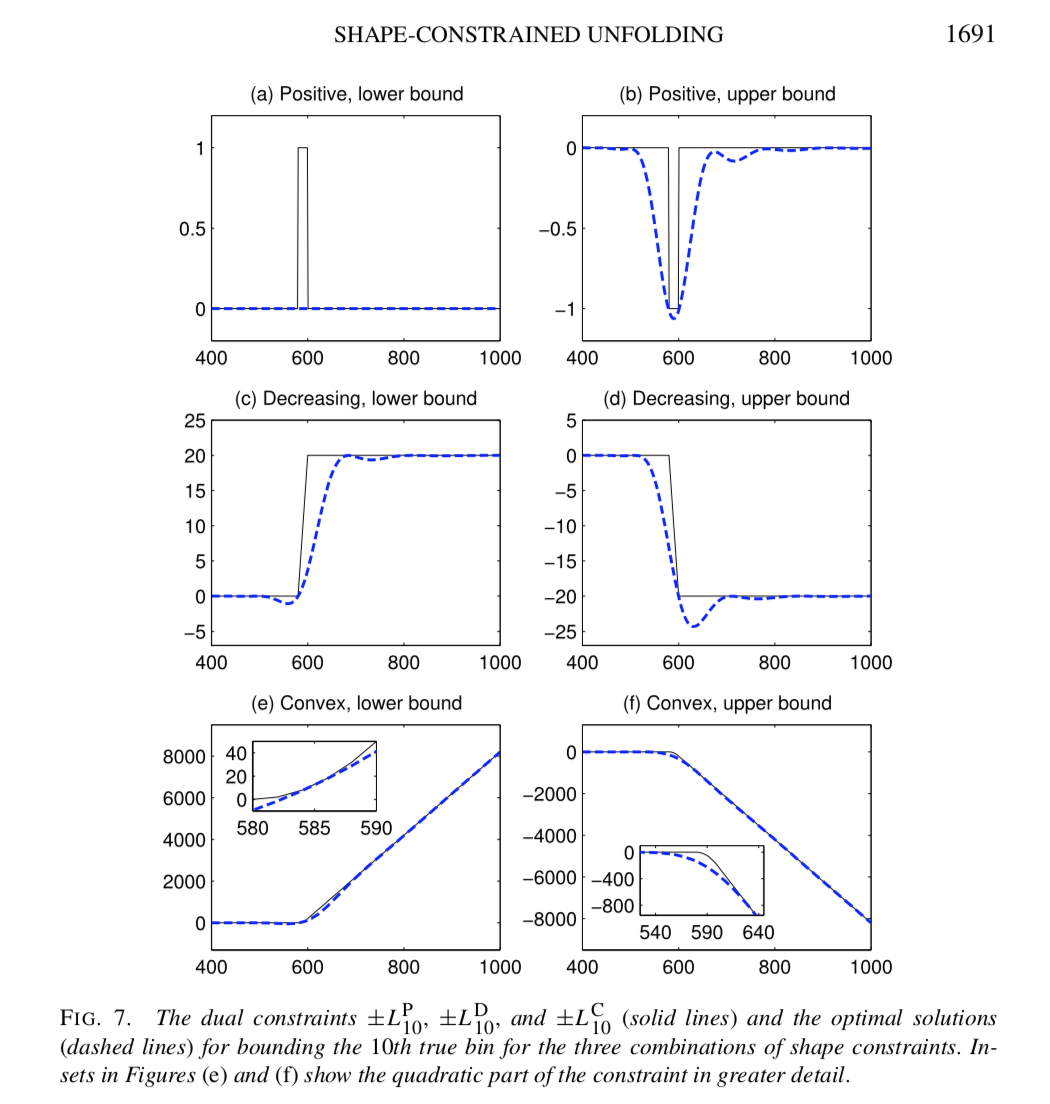

Kuusela, M., and P.B. Stark, 2017. Shape-constrained uncertainty quantification in unfolding steeply falling elementary particle spectra, Annals of Applied Statistics, 11, 1671–1710. Preprint: http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.00905